What in the heck am I talking about you ask? Why seal intestines, of course! That question posed a huge conundrum for me after the Museum successfully bid on a gut skin parka at Zemanek-Münster, a tribal arts auction company in Würzburg, Germany. Although, if I am being honest I had to worry about walrus, bowhead and beluga whale, and caribou intestines as well. The questions of exactly whose entrails made up the parka, its country of origin and its age had to be answered before we could import the object into the United States. It took three months and in the process its provenance shifted from one side of the North American continent to the other.

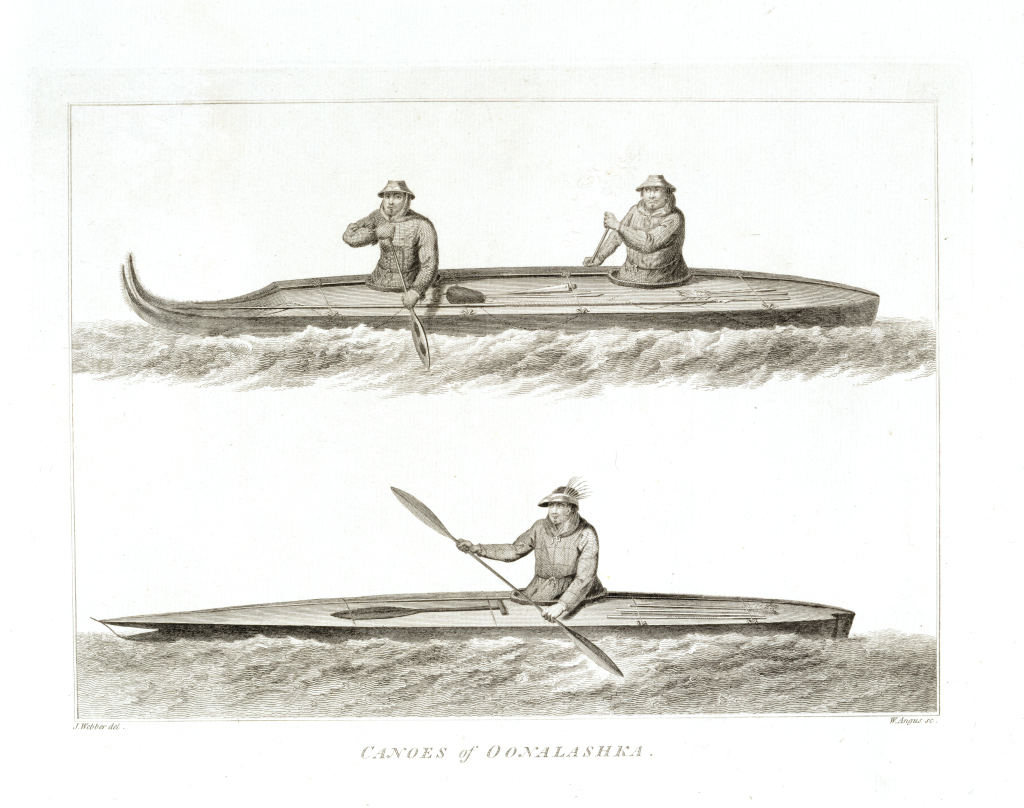

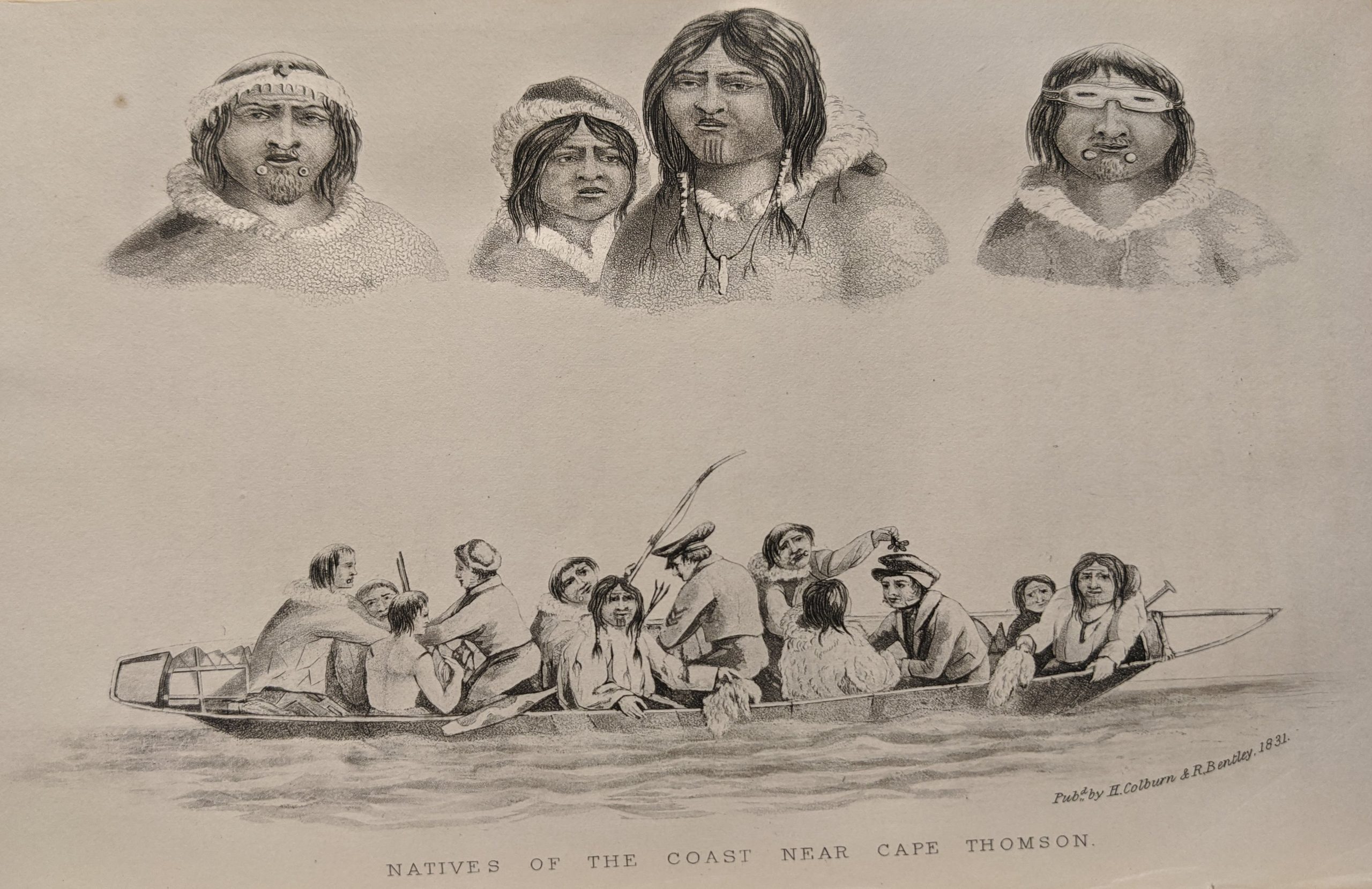

It all started in October while I researched the native populations of King Island, Kotzebue Sound and Huntingdon Island for the Museum’s Indigenous People’s Day on November 9th. I was primarily interested in how native Alaskans used the umiak, kayak and baidarka* to hunt which led me to study their tools and clothing as well. Using internet sites like the Smithsonian’s Department of Anthropology Collections (https://collections.nmnh.si.edu/search/anth/) and the Alaska Native Collections of the Smithsonian’s Arctic Studies Center (https://alaska.si.edu/index.asp) taught me a lot about the objects in our collection as well as native terminology. One of the words I learned was “kamleika” which is actually the word Russian traders used for the gut parkas worn by Arctic peoples.

I quickly identified several images in our collection that showed Aleut hunters wearing gut skin parkas and a few traditional hunting tools like spears, floats and seal retrievers. One day I stumbled across the Zemanek-Münster auction of a “Traditional men’s rain parka “kamleika” – Canada, Greenland, Inuit.” Finding items like this at auction is rare and they usually aren’t in a price range we can afford. With an estimate of €3,000 to €8,000 this one was and experience has shown me that auctions at lesser known houses that occur late in the year sometimes gives institutions like ours a fighting chance at acquiring these rare sorts of items.

Our collection holds five Arctic boats but very few items documenting the people who used them–and for goodness sake we’re not a boat museum we’re a people museum, it says so right in our name. We needed this parka and I was determined to get it. I immediately forwarded the auction listing to our Vice President of Collections and Programs, Lyles Forbes. Thankfully Lyles and the rest of the Museum’s collections committee agreed that we should try and acquire the parka. I placed a max bid of €3,200 and crossed my fingers. Thankfully my hunch proved correct, no one bid against us and we acquired the parka for the minimum bid of €3,000.

After completing the purchase I contacted Masterpiece International, a fantastic company in Herndon, Virginia that specializes in international art shipments. My contact at Masterpiece, Museum Services rep Amanda Otto, immediately stated we might have to acquire specialized permits in order to ship the parka to the United States–something I must admit I hadn’t thought about since the auction listing indicated it had originated in the US (the provenance listed was “Taylor Dale, Santa Fé, New Mexico”). Then she blew my mind–she asked me to provide her with the genus and species of the animal whose guts were used to create the parka. CRAAAAPPPP!!!!! (I actually used a slightly stronger word but I’m trying to keep this clean people). I had absolutely no idea how to answer that question.

I immediately began researching the types of animals typically used to construct gut skin parkas and was able to rule out whale and walrus because of the width of the parka’s bands. That left me with six types of Arctic seal (harp, hooded, ringed, bearded, spotted, and ribbon) plus all their various subspecies. Obviously where and when a parka was created greatly affected its manufacture–and gut skin parkas were created by every sea-hunting people in the Circumpolar North.

My research and my gut (sorry, couldn’t resist) told me the parka was most likely constructed with bearded seal intestine but I had to be sure–otherwise I would be lying to the Federal government! At that moment I made a decision that ended up completely changing the object’s history–I decided to try and track down the former owner identified in the auction listing. Thanks to the wonders of the internet I was able to find him and send an email explaining my predicament. As it turned out, the former owner, Taylor A. Dale Tribal Art, had not carried a gut parka in their inventory for many years but they promised to search their archival records for information that might help us.

In the meantime my research kept me vacillating between bearded, ringed and spotted seals, each of which presented their own problems with regards to permitting. The two permits we had to worry about were CITES and a Marine Mammal Permit. CITES, the acronym for Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, relates to the rules regarding the international trade of wild animals and plants. The Marine Mammal Permit relates to the Marine Mammal Protection Act and the Endangered Species Act. Any product containing parts of marine mammals requires an MMP and the processing time is typically four to six months. Thankfully the auction company was able to contact the German government and they determined we didn’t need a CITES permit (on the assumption it was Erignathus barbatus). With CITES ruled out Amanda began contacting art shippers and customs agents in Germany and New York**. She put me to work compiling the National Marine Fisheries Information Sheet and creating an Attestation to Historical Significance which were both required for the Marine Mammal Permit.

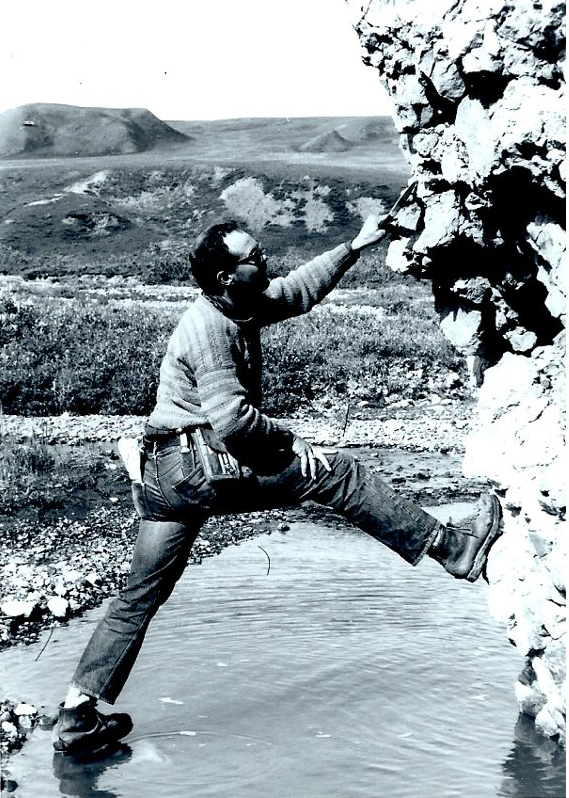

Then an email arrived and everything went south, nope north–extremely north–and west. The files at Taylor A. Dale Tribal Art revealed that they had acquired the parka from a retired geologist who had purchased the parka in Point Hope, Alaska (not Greenland!) in the 1960s. The company sold the parka in August of 2009 to a dealer in New York. This was the breakthrough I needed. Not only did it help narrow down the types of seal used, it attributed the garment to a specific culture.

With my pool of seals narrowed down to three I contacted our conservation department to see what kind of testing could be done on the gut to determine the genus and species of seal. Conservator Paige Schmidt contacted Ellen Carrlee at the Alaska State Museum for assistance. Carrlee, a specialist in gut skin and its use by native cultures, was confident the parka was made of bearded seal intestines. While ringed and spotted seals are caught in great numbers it is primarily for their meat, oil, and fur. Their intestines, being narrower and weaker don’t produce material strong enough to make parkas. Finally, with the manufacture narrowed down to bearded seal and the provenance information supplied by Taylor Dale we had everything we needed to get the permit. While Amanda coordinated the permitting and shipping arrangements we conducted research and an oral history interview with the “second” owner (the first being an unknown Alaskan native) to more fully develop the parka’s history.

The parka was acquired at Tikiġaq (pronounced Ti-ke-ruk in Iñupiaq) village at Point Hope, Alaska by noted geologist Gil Mull in June of 1964. The remote area is home to the Tikiġaġmiut (pronounced tick-ee-ah-my-oot) people. Point Hope, about two hundred miles north of the Arctic Circle and 330 miles southwest of Utqiagvik, Alaska, sits on a spit of land that sticks far out into the Chukchi Sea. Despite being described as “one of the most uncomfortable places in the world” (climate-wise), the location is advantageous because it brings migrating bowhead and beluga whales very close to shore. The area is also visited seasonally by walruses and bearded, spotted and ringed seals. These mammals provide an important source of raw materials for food, fuel, clothing and other manufactured goods. As proof of what a great location Point Hope is for the sea-hunting Inupiat, Tikiġaq is the longest continuously occupied settlement in North America.

Mr. Mull indicated that only 200 or 300 people lived at Tikiġaq in 1964 and described the area as “miserable, cold, icy and often fog bound.” He purchased the parka (called kapitaq in Iñupiaq) and several baleen baskets at the village store but stated that the village was so remote (it can only be reached by sea or air, even today) and so few people visited the area that the items were not being sold as part of a tourist trade but within the village population itself. He did say the parka was an older, well used item when he acquired it. After studying the materials used to create the parka and knowing that a Tikiġaġmiut hunter typically needed three new parkas each year we believe it dates to 1950-1960.

The staff here will continue to study the parka and are currently working with scientist Daniel Kirby at Harvard and Ellen Carrlee to fully identify the materials used in its manufacture. With luck we’ll be able to undertake the conservation of the piece soon so it can be used in our future programming. I definitely see a Gallery Crawl Station in its future!

*a kayak with two or three cockpits

**JFK is the designated Fish & Wildlife port