Over the last few months, I’ve listened to several podcasts discussing the potential of artificial intelligence (AI) to speed up and simplify work processes. During one broadcast, the host stated that if you aren’t investigating how to harness AI to perform the tasks associated with your job, you are in danger of becoming obsolete or being replaced and that no professional is immune from this possibility.

I will admit that I had previously discounted the use of AI because I had seen what a complete mess it can make of genealogical studies.1 Another drawback, one that seems insurmountable, is that the historical information curators and researchers typically use, things like rare books, documents, and manuscripts, aren’t available digitally and aren’t accessible to AI programs.2 Worst of all, AI’s current reliance on the internet means it considers ALL the information it locates, whether factual, erroneous, or irrelevant. This means an AI program’s responses, at least to history-related questions, will more than likely contain factually incorrect information or false suppositions.

Despite these problems, I do see the potential of AI, so when the podcast host suggested starting the learning process by simply asking a question that mattered to me — one I didn’t think AI could answer — I was willing to give it another chance. At the time, I was researching several artworks in preparation for a tour with the Naval Order of the United States, so I decided to investigate how AI could help with that work.

I had several goals for my first in-depth AI inquiry project — goals I assumed were simple. First, if I provided an AI program with a link to a web page that contained all of the information it needed, could it take in the information, distill it, and formulate a factually accurate response? My second goal was a little more abstract: could an AI program analyze an artwork and accurately describe the scene using the details provided by the artist, and, by extension, could it suggest a possible artist when an artwork was unsigned?

The AI program I chose to test was Grok3, mainly because it was getting a lot of positive reviews at the moment I decided to take another dive into the world of AI. With my first goal in mind (could AI provide a factually accurate response if I provided a link to a web page that contained all of the information it needed to answer my question), I asked Grok to tell me about a painting in our Collection. The result was an unmitigated disaster I can’t even begin to describe. The upside is that it uncovered a problem in the coding of our online catalog that prevents AI programs from reading our catalog pages.3

Knowing that Grok wouldn’t be able to meet my first goal until the problems with our online catalog were remedied, I moved on to my second, more abstract goal — can an AI program analyze and describe a painting and suggest the possible artist of an unsigned work? Naturally, I assumed Grok wouldn’t respond well to this question, but I ended up being pleasantly surprised. We had a fascinating and thought-provoking conversation that actually led to a change in the artist attribution of the painting we investigated.

The Victim

Historical Background of the Action4

During the early years of the American Revolution, the French clandestinely supported the American colonies. This changed on February 6, 1778, when the two countries signed a treaty of alliance. By April, the French had dispatched a fleet of 12 ships-of-the-line and five frigates under the command of Comte Charles Henri d’Estaing to support military operations in the United States. By early August, d’Estaing’s fleet and a British force under Admiral Richard Howe were maneuvering for battle off Narragansett, Rhode Island. That battle never occurred thanks to a hurricane that swept up the east coast and raged for several days.5 The stormy weather dispersed and jumbled the fleets together and severely damaged many vessels’ rigging.

As the fleets maneuvered to reform, enemy ships encountered each other and several single-ship actions occurred, including a battle between HMS Isis and Le César, the flagship of famed explorer Comte Louis Antoine de Bougainville. Approximately 70 miles northwest of Sandy Hook on August 16th, around noon, the two ships sighted each other, and a mutual chase began. The British had a real “oh s–t!” moment when they realized their quarry, and pursuer, was a French 74-gun ship. Isis only had 50 guns. The British captain, John Raynor, immediately tacked away, but Le César was a fast sailer and caught up with Isis about four o’clock that afternoon.

The French ship immediately hoisted a flag and fired a warning shot to leeward. When the British didn’t respond, Le César fired a broadside at the smaller vessel. Captain John Raynor described the broadside as “ill-served and ill-directed” (and possibly overcharged), so Isis escaped serious damage. When Le César passed Isis’s quarter, the French captain put the ship “in stays” (i.e., slowed down to change course) and Raynor responded by putting Isis’s helm hard to starboard. The British gun crews poured double-shotted cannon fire into the French ship as Isis maneuvered across its bow. The crew’s aim must have been effective because Raynor said the British fire “had an amazing effect” and caused the French to instantly stop “their huzzaing which they had been doing a great deal before.”

Raynor’s maneuver placed Isis on Le César’s leeward side, which various sources report had not been prepared for the action, possibly because the rough sea state prevented the lower gun ports from being opened. Other sources reported that the leeward guns were blocked by stacks of lumber that hadn’t been thrown overboard when the ship beat to quarters. Whatever the situation, the British maneuver brought the two ships within “half a pistol shot,” and they began pounding each other with cannon fire. Captain Raynor believed the British were out-firing the French, but admitted that at one point the concentration of Le César’s fire on Isis’s bow “made the forecastle so hot there was no standing upon it.”

Roughly an hour and a half into the action, Le César’s wheel was shot away. Although the French believed they could compel the smaller British ship to surrender, the appearance of two English ships convinced the French captain, Joseph-Louis de Raimondis, or one of his lieutenants,6 to quit the action, and Le César sailed off before the wind. The extensive damage to Isis’s masts, yards, sails, and rigging prevented the British from pursuing the fleeing vessel. As evidence of the intensity of the action, the Caledonian Mercury reported that Isis had 400 shot holes in her main topsail, 130 in her mizzen topsail, and 120 shot holes in her mizzen staysail. Amazingly, Isis only had one man killed and 15 wounded.

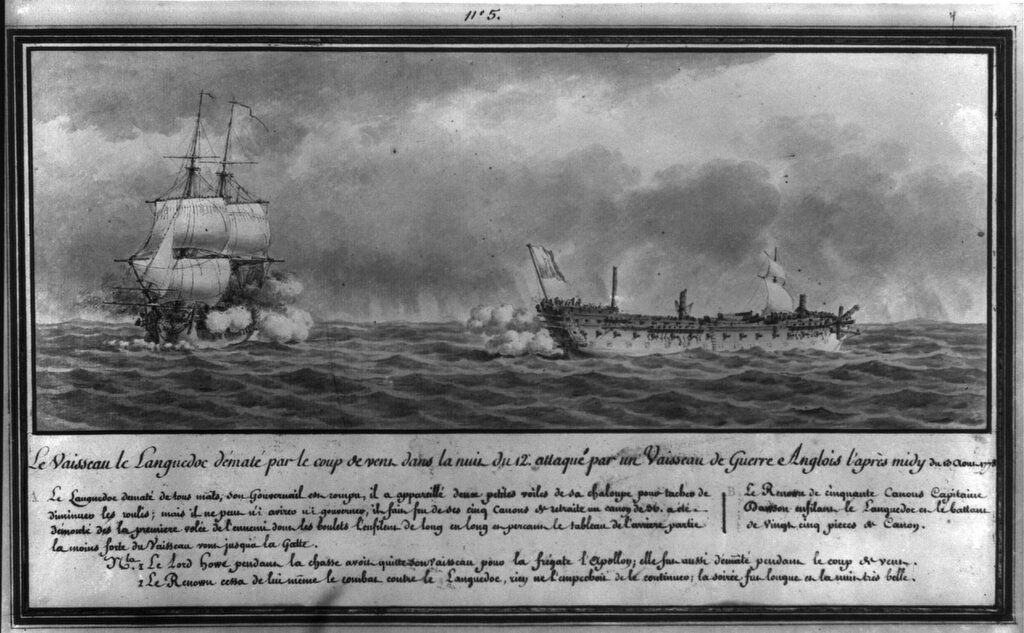

The Action Depicted by the Artist

In the painting, the artist has created a sequenced narrative account of the engagement between HMS Isis and Le César. It shows three stages within the course of the action and reads from right to left, an interesting and important aspect of this painting that you don’t often see. At the right, both ships appear undamaged, and the fighting tops are crowded with men. Both ships are firing — Isis on the starboard side and Le César on the port. Isis’s position on the canvas indicates the British ship is in the act of crossing the French ship’s bow, which fits Raynor’s description of the opening stages of the battle.

At the center, the artist depicts the ships in a running action, both close-hauled on a starboard tack. Both vessels have damaged sails and rigging, and there are shot holes and other damage visible to their hulls. In portraying the ships side by side, the artist may have wished to show the closeness of the action and the much larger size of the French vessel. A British blue ensign draped over the stern and a red ensign flying from the mizzen gaff places the action after 5:15, which is when the ensign staff of HMS Isis was shot away, and another flag was hoisted to the peak of the mizzen gaff to signal that the British ship had not surrendered.7

At the left, the position of Le César’s sails indicates the French ship is sailing before the wind. This appears to reflect the final stages of the battle after the wheel has been shot away and the French have prudently decided to retire from the action.

The Artist

The artistic quality of the painting is relatively high, although previous cleanings have dulled the crispness of the work. The ships and rigging are rendered beautifully, as is the water, which the artist has painted to suggest movement and the remnants of the departing storm. The artist has used a restrained color palette of muted yet harmonious colors. The sky and clouds have been rendered in soft, diffused pastel colors, and the light is natural-looking with no dramatic spotlighting or highlighting, which suggests the artist was focused on realism and documentation rather than theatricality.

Unfortunately, the artist either didn’t sign the painting or it has been obliterated by past cleaning efforts. In 1979, Sotheby Parke Bernet & Company in New York attributed the painting to British artist Nicholas Pocock (1740-1821). The Keeper of Paintings at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, E. H. H. Archibald, felt “fairly certain” that the painting was a good early example of the work of British artist Thomas Luny (1759-1837). When the painting was accessioned, the Museum’s curators followed Archibald’s advice and have been attributing the painting to Luny ever since.

A Conversation with Grok3

As I mentioned earlier, I was studying/researching this painting in preparation for a tour when I became curious about how AI could assist with my job. To start the conversation and assess its abilities, I uploaded an image file and asked Grok3 to analyze the painting without providing any additional details about the work. While Grok didn’t analyze the subject well (it thought the painting featured four ships, not two in three different positions, and couldn’t identify the nationality of the French vessel), it did recognize the vessels were frigates or ships-of-the-line of the Napoleonic Wars or American Revolution engaged in “a battle or close maneuver on a choppy sea.” Grok also commented that the ships, one of which it recognized as British, were “framed by a calm sky with scattered clouds and a detailed rendering of the ocean, with waves adding dynamism to the composition.”

Grok also suggested several possible artists for the piece: Nicholas Pocock (1740-1821), Thomas Whitcombe (1752/1763-1824), Dominic Serres (1722-1793) and Robert Dodd (1748-1815). All of these suggestions are valid, but after considering the styles of each artist, Grok made its first conclusion:

After considering the options, I lean toward Thomas Whitcombe as the most likely artist. The painting’s precise ship rendering, balanced composition, and subdued yet effective use of color align with his style, particularly in his depictions of British naval engagements. The lack of intense drama or theatrical lighting sets it apart from Pocock’s more atmospheric works, while the detailed realism fits Whitcombe’s reputation for historical accuracy, often seen in his battle scenes commissioned for prints or records. Without a signature or further context, this is an educated guess, but Whitcombe’s influence on such maritime narratives makes him a strong candidate.

Interestingly, Grok asked my opinion of its conclusion and wanted to know if I had any additional details that might help refine its response. I obliged by correcting Grok’s mistakes about the subject matter and provided the date of the action and the names and nationalities of the vessels depicted. I then made the mistake of telling Grok that the French ship could be identified by “the white flag on the stern.”

It was at this point that Grok’s lack of historical knowledge and reliance on the internet failed spectacularly. In its analysis of the painting’s composition and subject, Grok stated: “The white flag on Le César’s stern suggests a moment of surrender or negotiation, consistent with historical accounts where the French ship, a 74-gun vessel, was captured by the British Isis (a 50-gun fourth-rate) after a fierce engagement.” Umm…nope, and umm….nope. The French naval ensign prior to 1789 was a solid white flag, and I’m pretty sure that no historical accounts state that Le César surrendered. Grok also incorrectly placed the scene of the action off Toulon rather than 70 miles off Sandy Hook, New Jersey. Unfortunately, these mistakes reinforced my opinion that AI, at least in its current form, is incapable of creating factually accurate responses to history-based questions.8

Since the historical facts of the battle weren’t the end goal of my current investigation, I corrected Grok and pushed the mistakes aside. As Grok and I continued our conversation, I realized that using AI does have an amazing upside for curators. Having a free-flowing, back-and-forth conversation or debate with an AI program can open your mind up to new ideas and possibilities you hadn’t considered before. In other words, AI helps curators think outside of the box. By the end of our conversation, Grok and I had developed a theory for a new, and highly likely, artist attribution for this painting–but it took both of us, working together, to do it.

The movement towards the development of the new attribution began when Grok accepted my historical corrections and used the new information to reassess the four artists it had suggested. This time Grok leaned towards Dominic Serres as the artist of the painting. It provided justification for its belief, but once again I had to correct its historical mistakes and in its regenerated response Grok no longer seemed quite so confident of its suggested attribution.

Reflecting on the evidence, Dominic Serres remains the most likely artist, but with a caveat. His documentary style and experience recording Revolutionary War naval actions — often with a British perspective — fit the painting’s focus on a specific, staged engagement. The calm presentation and ship detail align with his work, such as his depictions of British victories, even if this battle ended in a French withdrawal. The white flag as a national ensign, rather than surrender, reinforces the historical accuracy he might have aimed for. However, the smaller scale of this skirmish (compared to his larger fleet battles) suggests he might have tailored this piece for a specific commission or record, possibly under Admiralty influence.

Again, Grok asked for my opinion, so I mentioned Archibald’s suggestion that Thomas Luny might be the artist of the painting. Intrigued, Grok reanalyzed the painting considering Luny’s “style, career, and how it aligns with this work, while critically assessing the idea [that Luny is the artist of the painting]” and came to the following conclusion:

I think Thomas Luny could be a reasonable candidate for the artist, particularly if this painting dates to his apprentice years (late 1770s) or shortly after, when he might have experimented with sequenced narratives or less dramatic scenes. The detailed ships and atmospheric smoke align with his skill set, and his British naval connections could explain the focus on Isis. However, the calm composition and lack of his signature bold lighting make it less definitive than his later works like Battle of the Nile. Without a signature or provenance, it’s a plausible but not certain attribution—perhaps an early Luny piece influenced by Holman’s style or a commission from a naval account.

Reading Grok’s response I didn’t get the impression it was confident Luny might be the artist of the painting of Isis and Le César. HOWEVER! In its response Grok had mentioned a name several times that piqued my interest: Francis Holman. Thomas Luny was Holman’s apprentice between 1770, when Luny was just 11 years old, and about 1780. I had recently researched a Holman painting in our collection and realized the style of the two paintings was very similar. I asked Grok if it thought Francis Holman might be the artist of the painting and it immediately went to work analysing his style against the other artists we had considered previously.

Critical Considerations

Holman’s technique of showing ships in multiple positions is a rare and distinctive trait, setting him apart from contemporaries like Serres (who focused on broader fleet actions) or Whitcombe (more illustrative and chaotic). The painting’s focus on a single engagement’s progression, rather than a glorified victory, suits Holman’s documentary intent—especially given the battle’s inconclusive outcome (French withdrawal with two British ships approaching). His London-based career and connections to naval circles could have provided access to accounts of this event, even if it wasn’t a major triumph like Trafalgar.

The main challenge is Holman’s relatively short career and limited surviving catalog compared to Luny or Whitcombe. His death in 1784 might limit his later Revolutionary War output, but 1778 is well within his prime. The painting’s muted drama also contrasts with Luny’s later atmospheric style, which Holman influenced, suggesting this could be a purer example of Holman’s own approach before Luny’s flair took hold.

Comparison to Previous Suggestions

- Dominic Serres: While Serres’ calm, documentary style fits, his focus on larger fleet actions doesn’t match the sequenced narrative as closely as Holman’s specialty.

- Thomas Luny: Luny’s early influence from Holman is evident, but his later dramatic lighting and single-moment focus differ from this staged depiction. If this were an early Luny under Holman’s tutelage, it might reflect Holman’s style more than Luny’s mature work.

- Thomas Whitcombe: Whitcombe’s illustrative precision is close, but his later career (post-1780s) and chaotic battle scenes don’t align as neatly with the painting’s calm progression.

Grok’s conclusion found that Francis Holman is “a highly plausible artist for this painting,” stating:

…your observation about his use of multiple ship positions strengthens this case significantly. The sequenced depiction of Le César and Isis at three stages of the August 16, 1778, battle off New Jersey—approach, combat, and withdrawal—matches Holman’s distinctive style perfectly. The detailed ships, calm composition, and historical context within his active period (1770s–1780s) support this attribution. The white French ensign and subdued tone reflect his documentary approach, likely aimed at recording the event for naval or commercial patrons.

Like any self-respecting curator, Grok did place the caveat that “without a signature or provenance, it’s not definitive, but Holman’s signature technique gives him an edge over the others.” The “signature technique” Grok is referring to is Holman’s tendency to create paintings with a compositional narrative of his subject. In other words, he shows multiple views of the same vessel or vessels in different positions creating a narrative of movement over a period of time. As I researched Holman’s background I discovered several artworks dating from the same time period and location which reveals that Holman was aware of war events in the United States:

- Holman displayed a painting titled The attack upon the town of Newport, Rhode Island, by the French fleet under the command of Count d’Estaing in August 1778 at the Royal Academy of Arts in April 1779.

- The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art holds a photograph of a 1778 Holman painting titled British Men O’ War in a Rough Sea off the Coast. The 1778 date certainly makes one wonder if the scene depicts British ships caught in the August 11-13 storm that preceded the August 16 battle between Isis and Le César.

So, Grok’s conclusion and my conclusion (after I studied more of Holman’s work) align. We both believe it’s possible that Francis Holman is the artist of the sequenced narrative battle of Isis and Le César. Just for fun, I also had conversations about the painting with ChatGPT and Perplexity, and both came to the conclusion that Francis Holman was a strong candidate as the artist of the painting, though I do wonder if having to walk each program through the analysis of the painting tilted their conclusions in Holman’s favor.

I did have a good laugh when ChatGPT stated: Painting B very likely belongs to Francis Holman, or at minimum to a painter strongly influenced by his narrative and technical approach. Oh, really? Do you mean someone like Thomas Luny?9 At any rate, I decided to update our catalog record and add Francis Holman as a potential artist of the painting, although I did leave the attribution to Thomas Luny intact for prudence’s sake. Research will continue and maybe someday a signature or other clue will reveal the true artist of the painting.

As for the goals I set for my AI investigation I now have an answer for both. Obviously the problem of AI programs not being able to see/read the records in the Museum’s online catalog will eventually be fixed so I can’t blame Grok for its inability to do what I asked (i.e. review a catalog record and spit my own research back at me correctly). You can rest assured that once our coding problem is fixed I will be testing this question again.

As for my second two-part goal, the answer to the first part (can an AI program analyze an artwork and accurately describe the scene using the details provided by the artist) is an emphatic NO. I asked Grok3, Perplexity and ChatGPT to analyze the painting and describe it and all failed miserably. I had to teach each program baby-step by baby-step to recognize the most basic artistic, maritime and historical facts but none of the generative AI programs progressed to the point of being able to produce an accurate description of the artwork.10

AI’s lack of understanding of maritime history, technology and terminology and its inability to think and see like a human — especially a human with the discerning and detailed eye of a trained curator — means I’m not going to be replaced by AI anytime soon (at least when it comes to analyzing art). This being said, AI has the wonderful potential of helping a curator or researcher think outside of the box when it comes to analyzing art. I’m not sure I would have ever considered Francis Holman as the potential artist of the painting on my own, and I don’t think Grok3 would have considered Holman without my suggestion.

UPDATE!

As is typical with unsigned paintings, mysteries appear, questions are asked, a possible solution presents itself, another mystery appears in the process and another possible solution presents itself. This time AI had nothing to do with the research that presented the new mystery, it was just good old fashioned detective work.

Just follow me here because this is a tough one.

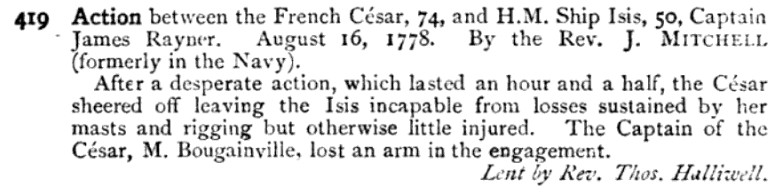

If you read the footnotes of my post you’ll know that footnote 9 mentioned a sketchbook created by Thomas Luny between 1777 and January of 1780 in the collection of the National Maritime Museum (NMM) in Greenwich, England. In that sketchbook there were several pages of notes and sketches of HMS Joy. The data contained in NMM’s catalog record led me to believe that Joy was a mistranscription of Isis. I sent a message to NMM and recently I received a response from the curator of art, Katherine Gazzard. She stated that I was correct, the sketches and ship details do show John Raynor’s Isis. Before I responded to Ms. Gazzard’s message I did a quick search to see if Thomas Luny had painted a portrait of HMS Isis. I had already studied Luny’s catalog raissoné and hadn’t found one but I figured another search couldn’t hurt. I wasn’t wrong. What I stumbled across was an entry in the catalog of the 1891 Royal Naval Exhibition:

The catalog entry indicates that a painting with a similar description to ours was painted by a reverend named “J. Mitchell.” I began researching reverends named Mitchell in England (there were many!) to see if any were artists and found none. I did locate a British artist named J. Edgar Mitchell, but he primarily worked in watercolor and typically created rural scenes. The few images I found showing naval battles by Mitchell exhibited a completely different artistic style so I’m pretty sure J. Edgar Mitchell is not the artist of our painting.

Consequently, I don’t know what to think of the attribution of a painting of Isis and Cesar to a Rev. J. Mitchell. Could it be a mistake made by the lender (another reverend named Thomas Halliwell)? Ships and rigging are difficult to paint accurately and the quality of those things is good in our painting, certainly much better than those drawn by an amateur with no other artistic works to his name.

Whatever the case, when I looked at the sketches of Isis in NMM’s sketchbook they certainly look like the working notes for a painting of Isis. The ship had visited both Plymouth and Portsmouth in 1779 and 1780 while Raynor was still captain so Luny may have visited the ship. His notes are VERY specific. They include dimensions of many parts of the ship and even gives coloring notes for specific parts of the vessel — some of which match the coloring of our painting. For example, on a sketch of the stern he states “all above the ballcona sable” and “window frames sable.”

Another sketch shows a side profile of Isis’s stern carvings, a starboard broadside view including a line above the top rail that says “hammocks,” and color notes that match our painting (i.e. a sable stripe above the upper gun ports). All of these features are extremely similar to the view of Isis shown in the central scene of our painting.

Captain Raynor and Isis did participate in several other actions during the American Revolution, but the 1778 action with Le César appears to have been the most significant of his career. This makes one wonder if Raynor commissioned a painting of the battle when he returned to England in 1779 or 1780. The date of the sketch book certainly overlaps this time period. Unfortunately, Raynor died at the end of July 1780 (around the 28th?), so it’s possible he never saw or received the finished product.

Mysteries, mysteries, mysteries! As it turns out AI made exactly zero contributions to the research — in fact, it might have just led me on a wild goose chase away from E.H.H. Archibald’s initial hunch that Luny was the artist of the painting. Francis Holman certainly can’t be ruled out as the artist and neither can the Reverend J. Mitchell. At any rate, I still think the discussion with Grok was interesting and believe it can help curators and researchers think outside of the box, but, in the end, only good, old-fashioned detective work is a curator’s best option.

1 For example, AI appears incapable of discerning between individuals with the same name.

2 Every book and document in every repository in the world would need to be digitized and made available on the internet for AI to do a comprehensive and effective search, but even then mistakes made in historical documents would have to be sorted out by a researcher to establish historical accuracy.

3 If you are interested in knowing what was causing the disaster I waded into, this is the response I received from our Director of Digital Transformation to my long and whiny email: “I think I see what’s happening. Our catalog pages open just fine in a regular browser but sometimes reports “blank” or missing when you ask an AI assistant. That’s because the site loads the item details with behind-the-scenes code that only runs inside a full JavaScript enabled browser. Automated tools that don’t run that code can’t see those details. We should be running pre-rendering that’s supposed to create a plain-text version of each page for search engines and AI tools…but this does not appear to be working currently. Until this is fixed, AI answers about our collection, even with a URL for reference, may be hit-or-miss. If an AI assistant seems confused, it’s probably guessing from an old snapshot or incomplete information.”

4 Just for clarification, all of the historical research used to create the description of the battle was conducted by me. No AI program I tried was able to contribute any relevant historical facts to the research.

5 Early American Hurricanes 1492-1870, David Ludlum, pages 27-28.

6 A report from Boston dated August 24 stated the French captain had lost his right arm in the action. The Public Advertiser of December 19, 1778 contained an article reported in Newport on October 8 that the captain of Cesar had died of wounds he received during the August action the previous week.

7 The loss of the British ship’s flagstaff may be why the French believed the British ship had struck

8 Since everyone always discusses AI’s ability to learn, I always made sure to correct Grok whenever it made a mistake. It did incorporate those corrections into an updated response so maybe the next person that asks about the battle between Isis and Le César will get more accurate information!

9 I have not found anything to disqualify Luny as the artist of this painting. I did discover that Luny may have been traveling in France in 1777-1778 which is documented in sketchbooks in the collection of the National Maritime Museum: https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-123751 . Interestingly, two sketches in the same sketchbook give views of the bow and stern of a 50-gun ship named Joy under “Capt. Rayner.” There has never been a Royal Navy ship named Joy which makes one wonder if Joy is a mistranscription of Isis. If they do show Isis it may be indirect proof that Luny is the artist of the painting. https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-123769

10 If you want to see how I described the painting here is a link to the online catalog record: https://catalogs.marinersmuseum.org/object/CL11172 .