The American Civil War was the first modern total war. North and South often relied on new technologies in their quest to achieve victory. Few other aspects of the Civil War witnessed such a reliance on new tactics and tools as the war along the rivers, coasts, and oceans. The South was obviously at a disadvantage as an agrarian society faced with waging technological warfare. This situation became very apparent when the Confederate leaders realized that their all-important commercial connection with Europe was threatened by the Union blockade. Immediately, the Confederacy sought new or otherwise experimental equipment necessary to counter the Federal advantages. The Union would react by using its industrial strength to counter and then overwhelm Confederate shipbuilding efforts.

All of the recent technical changes in ordnance, motive power, and ship design were observed and acknowledged by several pre-war American politicians, naval leaders, scientists, and engineers. France and Great Britain had begun to build ironclads. When the Confederacy was initially organized, the new nation was fortunate to follow the forward thinking of Floridian Stephen Russell Mallory. Mallory was the former chairman of the U.S. Senate’s Naval Affairs Committee and was quickly named the Confederate Secretary of the Navy. The secretary immediately realized that the South could never match the North’s superior shipbuilding capabilities unless a new “class of vessels hitherto unknown to naval service” was introduced to tip the balance in favor of the Confederacy. Mallory knew that iron-cased warships armed with the most powerful rifled guns and rams could destroy the Union’s wooden navy.

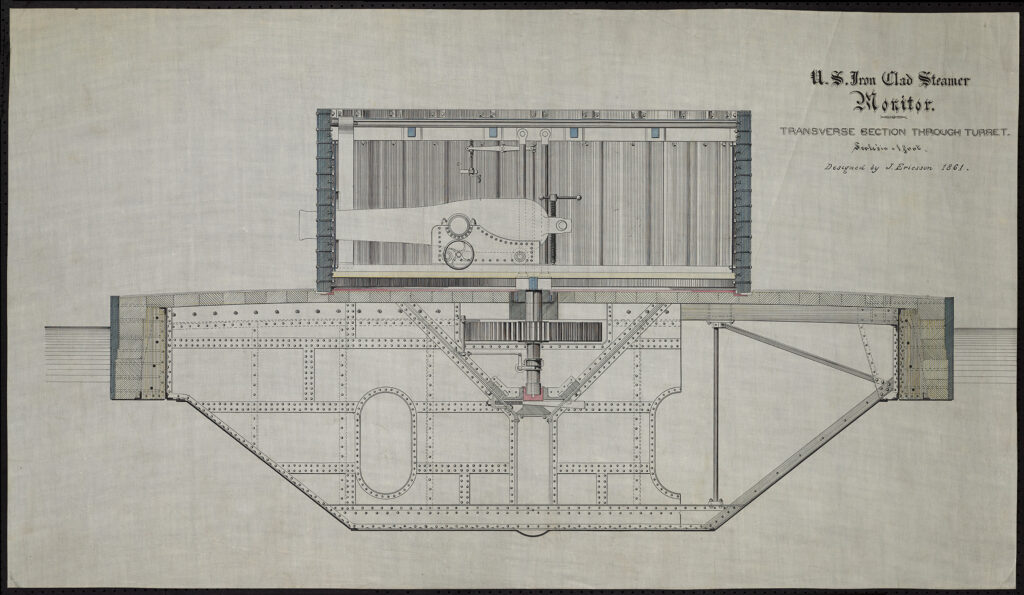

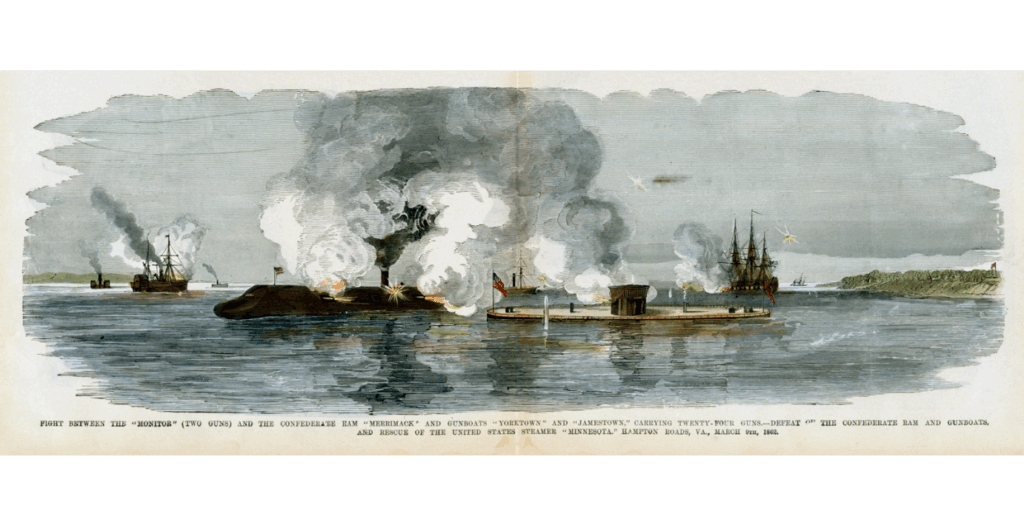

When the U.S. Navy abandoned Gosport Navy Yard in April 1861, Mallory found the wherewithal to begin construction of ironclads. The scuttled USS Merrimack was slowly converted into the ironclad ram, CSS Virginia, and Mallory initiated the construction of four other ironclads to defend the Mississippi River. News of the Southern ironclad building program made its way north, prompting the Union to begin building iron-cased warships, particularly USS Monitor. The construction of these two ships would result in the first battle between ironclad warships and begin a revolution in naval warfare.

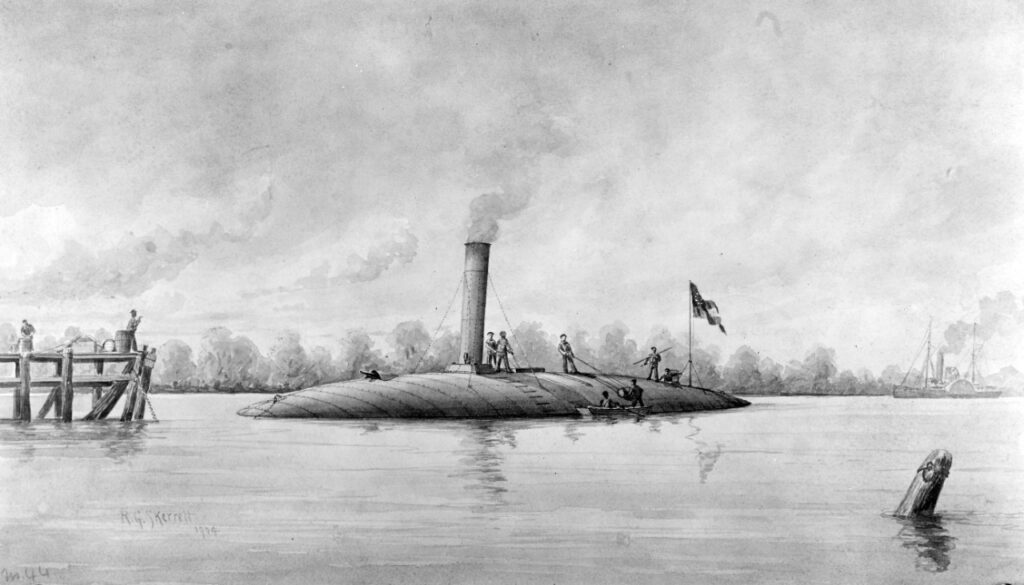

Monitor and Virginia influenced ship construction for the next 50 years. North and South concentrated on building more of their modified ironclad designs. Once ironclads appeared to be the key to naval success, the South’s agrarian society struggled to match Northern industrial strength. The two ironclads under construction at New Orleans typified the problems faced by the Confederate shipbuilding program. When Flag Officer David Glasgow Farragut attacked the masonry coastal forts, Fort St. Philip and Fort Jackson, defending the riverine approach to New Orleans, CSS Louisiana engines were not operational, and it could only serve as a floating battery. CSS Mississippi was still under construction. The ram CSS Manassas, privately converted from the tug Enoch Train, was an ill-conceived warship and covered by only one inch of iron plate. Nevertheless, it was the only functioning ironclad defending New Orleans. All three ironclads would be destroyed: Manassas, riddled by shot from Mississippi, ran aground and was burned, while Louisiana and Mississippi were scuttled by their own crews to prevent their capture.

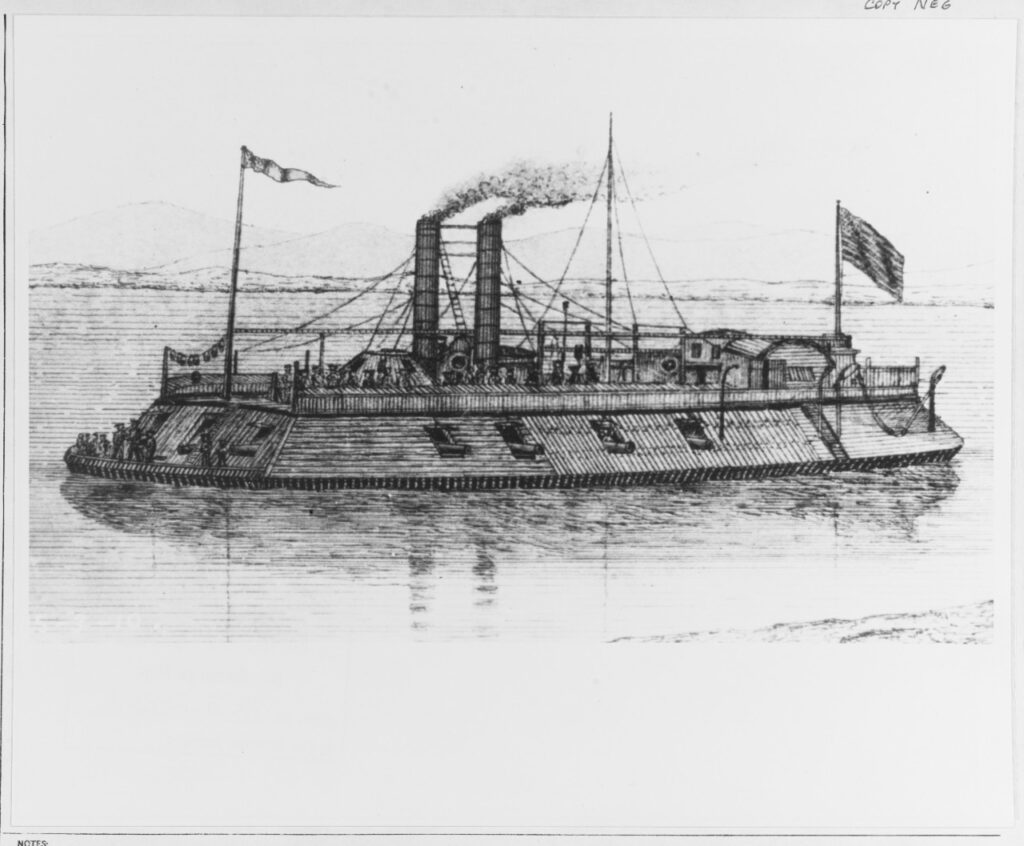

Obviously, the Confederacy was unable to defend its harbors, coastline, and rivers in early 1862. February 1862 would witness the first major naval actions in the Western theater. Major General U.S. Grant relied upon Flag Officer Andrew Hull Foote to attack Middle Tennessee. Foote’s ironclads overwhelmed Fort Henry on the Cumberland River; yet, these ironclads were repulsed during an attack against Fort Donelson on the Tennessee River. The Federal casemated, rear paddle wheel ironclads, designed by Naval Constructor Samuel Pook, were found not to be shot-proof as they were protected by only 3.5 inches of iron.

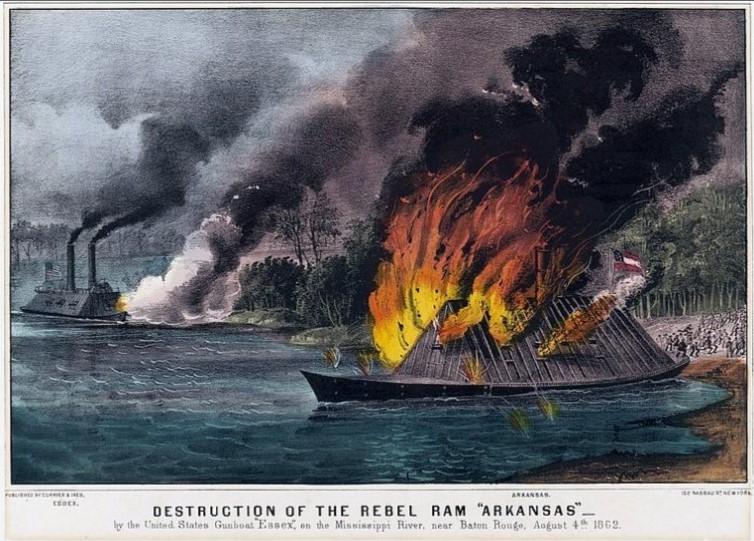

Nevertheless, the Confederates did not have any vessel to counter these Union ironclads until CSS Arkansas emerged from the Yazoo River. Originally laid down at the Shirley Yard in Memphis, Arkansas was moved to Greenwood City, Mississippi, and completed under the direction of Lieutenant Issac Newton Brown. Only partially plated with railroad T-rails with an almost perpendicular casemate, Arkansas steamed through the entire Federal fleet above Vicksburg on July 15, 1862. The Confederate ironclad damaged the USS Carondelet and made it to Vicksburg. Arkansas was attacked at its mooring by the ironclad USS Essex and ram USS Star of the West. The melee failed to destroy the Confederate ironclad; however, Arkansas was eventually scuttled by its own crew due to engine failure.

The events of 1862 taught Union and Confederate leaders that ironclads were the key to naval victory. Naval Constructor John Luke Porter modified the Confederate ironclad into a smaller, lighter draft vessel more appropriate for riverine service and harbor defense. Nevertheless, the improved design could not resolve inherent problems: poor propulsion systems, construction delays, limited production of iron and machinery, an overtaxed transportation network, and the lack of skilled workers. Most of the ironclads laid down in 1862 would not be ready for service until 1864 as a result of Confederate shipbuilding challenges. Consequently, the South would only put 22 ironclads in the water. Likewise, Union ironclad production increased and evolved. USS Monitor may have been ‘the little ship that saved the nation,’ but there were numerous flaws in the design. Monitors were basically floating batteries, having to be towed from port to port. The ships were so unseaworthy that they had difficulty serving as blockaders. These monitors had limited firepower, inadequate gun elevation, and a slow volume of fire. John Ericsson and other designers strove to correct these problems with subsequent monitor classes. Two, three, and four-turreted ironclads, totaling 49 ships, would be produced in an effort to contest Confederate defenses and ironclads.

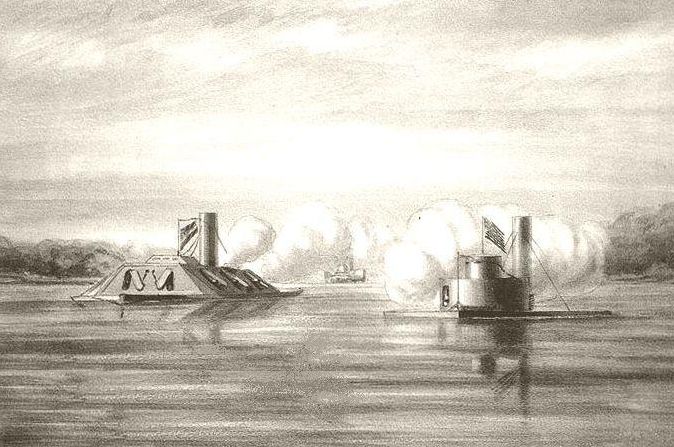

The new monitor and casemate ironclads were tested immediately in 1863. On January 31, 1963, CSS Chicora and Palmetto State struck at the blockading fleet outside of Charleston. These two ironclads damaged four Union vessels, but could not break the blockade. The only other Confederate to challenge the blockade in 1863 was the ill-fated venture of CSS Atlanta, which had been converted from the British blockade runner Fingal. The ironclad had excellent engines; however, the ship had a 16-foot draft, which limited movement through the shoals below Savannah. It was believed that Atlanta, armed with two 7-inch and 6.4-inch Brooke guns and a spar torpedo, could successfully encounter a Union monitor. On June 17, 1863, Atlanta made a foray into Wassau Sound below Savannah and ran aground as it approached two monitors, USS Nahant and Weehawken. These Passaic-class warships were armed with one XV- and one XI-inch Dahlgren’s. Weehawken approached within 300 yards of Atlanta. Four of the five shots struck Atlanta, breaking the Confederate ship’s casemate.

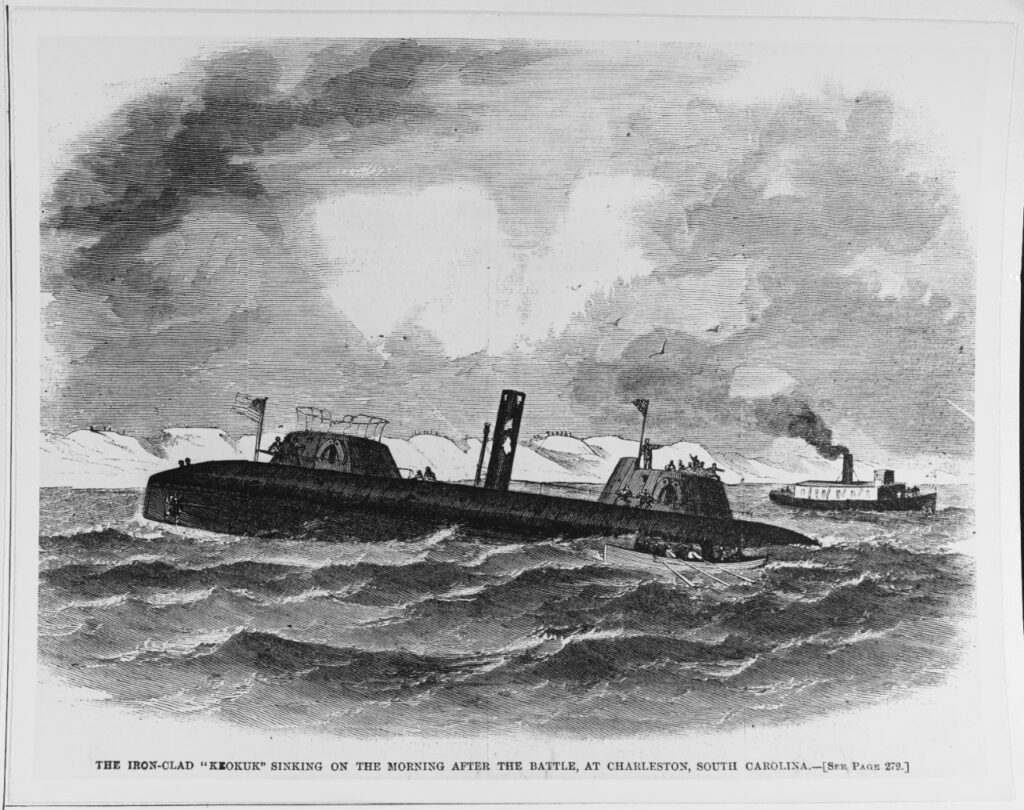

Although the XV-inch shell gun gave the Passaic-class the power to break through the six-inch iron plate shield of Atlanta, these guns did not give the Union ironclads the firepower to destroy well-organized coastal defenses. Nevertheless, Rear Admiral Samuel Francis DuPont took nine ironclads to attack Charleston, South Carolina. The fleet included seven monitors, the casemate CSS New Ironsides, and the tower ironclad Keokuk. General P.G.T. Beauregard had created an in-depth defensive system including torpedoes, two ironclads, and coastal forts mounting 77 heavy guns. Many of the Brooke rifles used armor-piercing Brooke bolts. On April 7, 1863, DuPont’s fleet attacked. Union ironclads managed to fire only 55 shots. In return, the Confederates struck the Federal armorclads over 400 times. Several monitors were severely damaged, and Keokuk sank. The engagement proved that monitors lacked the firepower to contest well-prepared coastal forts. The Federals now realized that the Federal fleet needed U.S. Army support to capture the remaining Confederate ports.

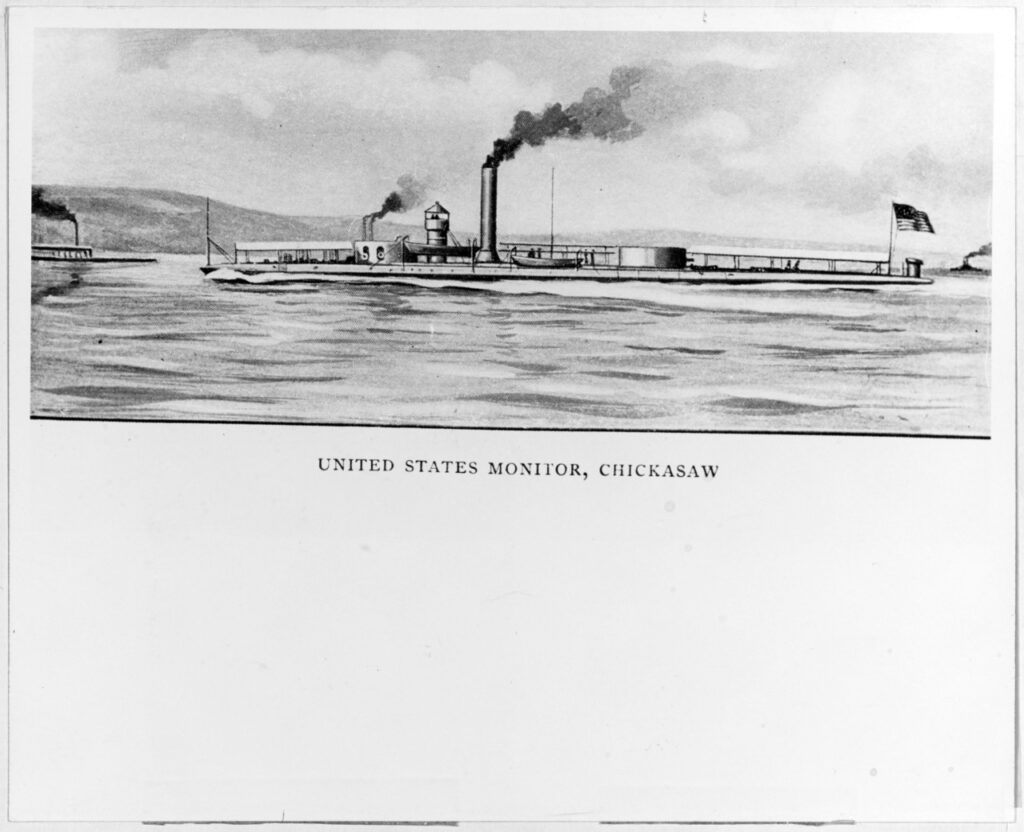

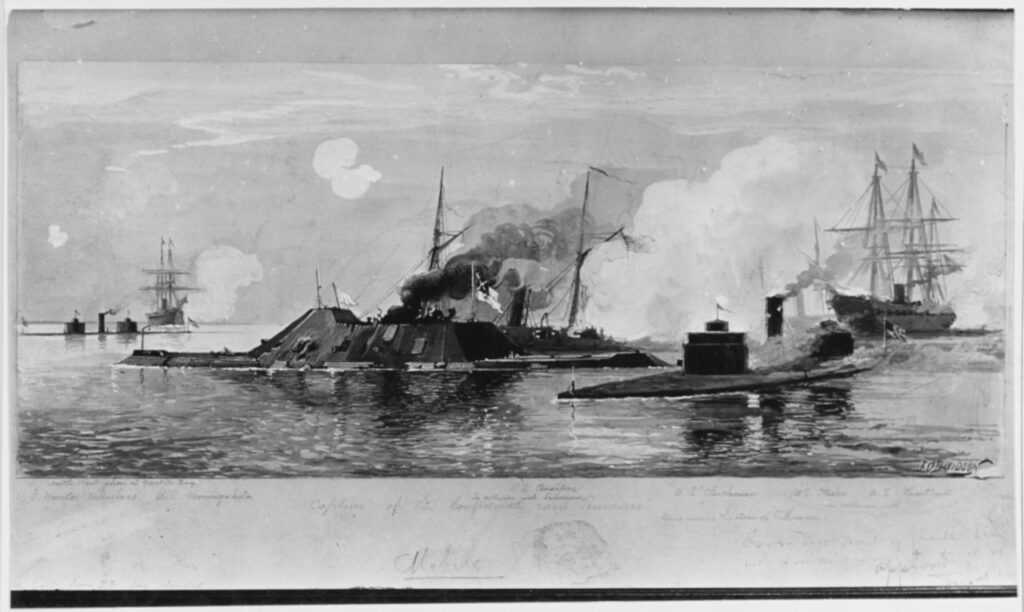

By 1864, the Confederates were able to launch several more effective ironclads, such as CSS Albemarle in the North Carolina Sounds and CSS Tennessee in Mobile Bay, Alabama. Albemarle did achieve success sinking USS Southfield off Plymouth, North Carolina, on April 19, 1864; however, the ironclad would eventually be destroyed by a spar torpedo on October 27, 1864. Meanwhile, Admiral David Glasglow Farragut organized an attack against Mobile Bay. Although one monitor, USS Tecumseh, was sunk by a torpedo, Farragut was able to pass the forts and then defeat the powerful Confederate ram, Tennessee. Tennessee was rammed three times; however, the monitors in Farragut’s fleet did the real damage to the Confederate ram. USS Manhattan came alongside and fired its XV-inch Dahlgren, which broke Tennessee’s casemate. The twin-turreted USS Chickasaw sent shot from its XI-inch Dahlgren’s at 50 yards, which rammed the port shutters, cut the exposed anchor chains, knocked the funnel over, and wounded and killed several men. Tennessee then surrendered.

The final ironclad engagement was a desperate attempt by the Confederate Richmond Squadron to destroy the Union supply base at City Point, Virginia. Federal shore batteries and the twin-turreted USS Onondaga blocked the path of CSS Richmond and CSS Virginia II. This last engagement was anticlimactic. Soon all of the Confederate ironclads in Savannah, Charleston, and Richmond were destroyed as the Confederacy collapsed.

Few facets of the Civil War more closely reinforce the technology and attrition themes than the war on the water. The war witnessed an overnight change to naval tactics. Boarding tactics and ‘Fighting Instructions’ became archaic and forgotten due to steam power, ironclads, revolving turrets, torpedoes, and rifled cannons. Secretary Mallory’s drive to create ironclads started the process that proved the power of iron over wood. The Union counterpunch, USS Monitor, resulted in a fleet of ironclads that helped to achieve victory while simultaneously creating a vision for future navies to follow.