In other blogs, we’ve talked about the goals of the Park as they pertained to planting. However, one of the main goals for Anna Hyatt Huntington (renowned sculptor and wife of Archer Huntington) was to have a wildlife sanctuary. She sculpted live animals, when she could, to give life and realism to her work. For several years, we had a permitted wildlife sanctuary in the Park! Of the projects from the early years of the Park, our wildlife endeavor was the longest, lasting until almost 1950.

Work on securing wildlife for the Park didn’t begin until a year after the start of a majority of the construction. The Lake was a big component of the wildlife sanctuary and accordingly, its completion was necessary before animals could come in. The first permit we applied for was with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) for a waterfowl enclosure in August of 1931. In that first application, we asked for 35 Canada geese to put in a goose range in the Lake. Dr. Albert K. Fisher, ornithologist and President of the American Ornithologists’ Union, served as our wildlife consultant. In August of 1932, he wrote that the goose range, “will be one of the finest, if not the finest, in the United States.”

In September of 1931, we filed our first wildlife sanctuary license with The Commonwealth of Virginia Commission of Game and Inland Fisheries. It was a five-year grant with the possibility of renewal in five-year increments. With this license, the Museum was not able to, “capture, kill and dispose of any species of wildlife or wild animals.” By October of 1931, the Museum requested an additional permit from the USDA to increase our waterfowl enclosure to include ducks and other waterfowl. The original hope to breed and hunt the waterfowl became an impossibility due to the sanctuary license. However, we got approval for an occasional permit for ‘nuisance species.’ In February of 1932, we asked for permission to host a fox hunt in the Park because they were disturbing the wildlife. Permission allowed us, “to have the fox, skunk, mink, weasel, possum, sharp shined hawk, cooper’s hawk, marsh hawk and great horned owl trapped, shot, or run with dogs on the property.” It is unclear if this hunt ever occurred.

One of the amazing things about the early years of the Park is that we explored all ideas. For example, in December of 1931, the State Superintendent of Game Propagation visited the Park to brainstorm. Ideas included introducing beavers from the Pennsylvania Game Commission (by February of 1932 we decided against it) and elk from Jackson Hole, Wyoming (we also decided against this idea).

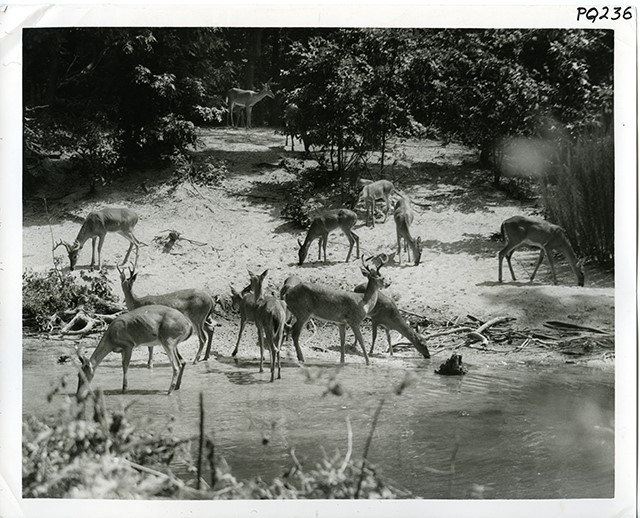

Perhaps, our most unique idea was to keep a deer park. Aptly named, Deer Park. The idea started with Anna. As I mentioned, she liked to sculpt live animals. In August of 1932, we wrote to Mount Pisgah Federal Forest Preserve in Asheville, North Carolina to request deer. They were much stockier than white-tailed deer and we bred them together to create the perfect specimen. One buck and three does came at the beginning of September by railroad. We also received two fawns from St. Charles, Illinois. The deer lived in a fenced enclosure in the Deer Park. But, deer don’t do very well in small spaces and food sources became an issue. By April of 1937, the deer population had risen significantly. We wrote to the State Game Department, “we are anxious to have some qualified person investigate to see whether or not the park is overstocked.” Spoiler alert: it was.

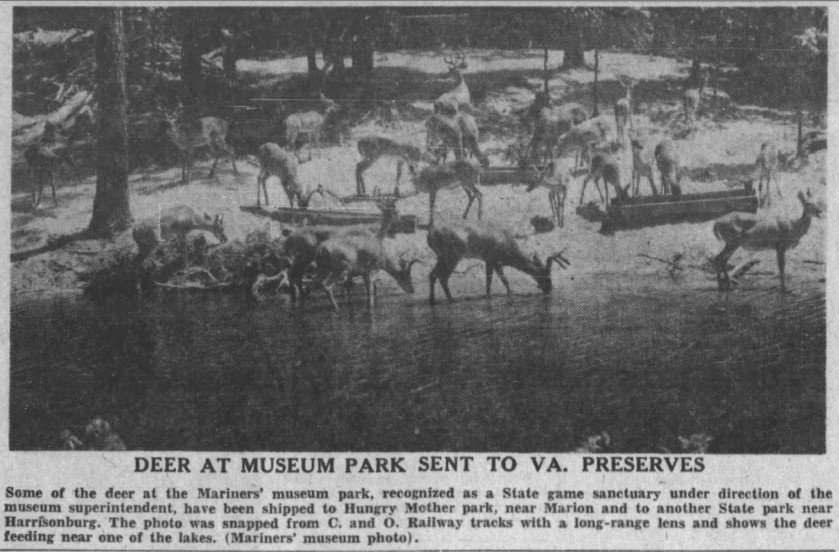

In September of 1938, the State Game Department came to the Park to assess the deer population. With 20 deer seen, the suggestion was to sell some of the deer to the Commission of Game and Inland Fisheries. By the following year, we began trapping and moving deer. Eight does and two bucks went to Hungry Mother State Park and six does to Harrisonburg. However, that was only a temporary fix. By June of 1941, despite many trappings, there were forty deer in the Deer Park (by comparison, we estimate that we have that many total in the entire 550-acres of the Park today). We gave the remaining deer to the Commission of Game and Inland Fisheries and on August 26, 1947, we gave the land from Deer Park to Warwick County to create a school and park.

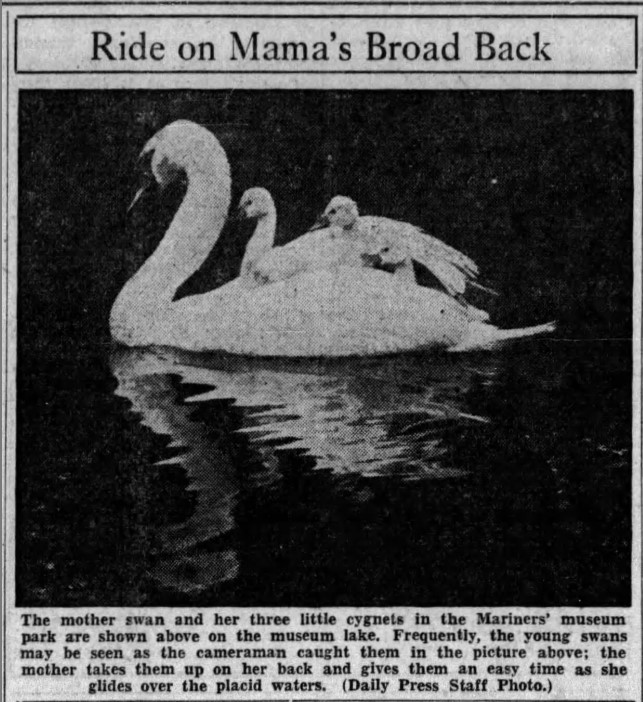

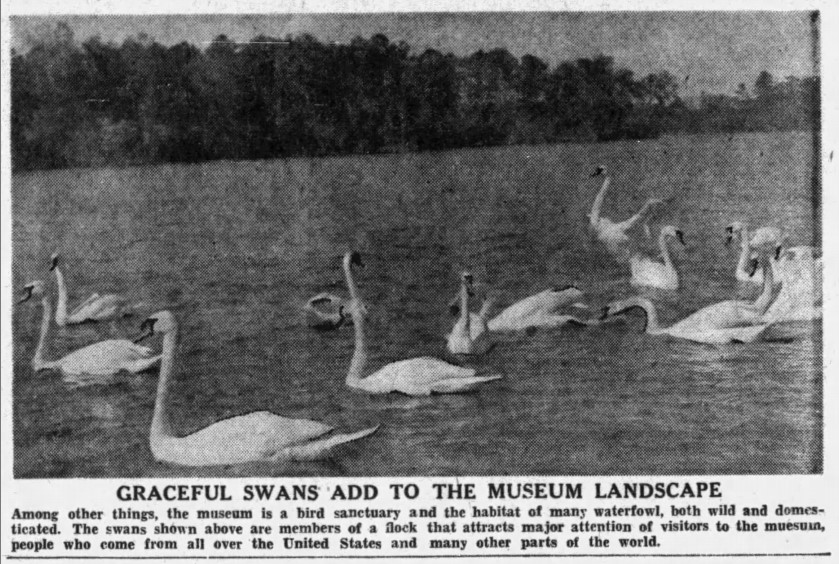

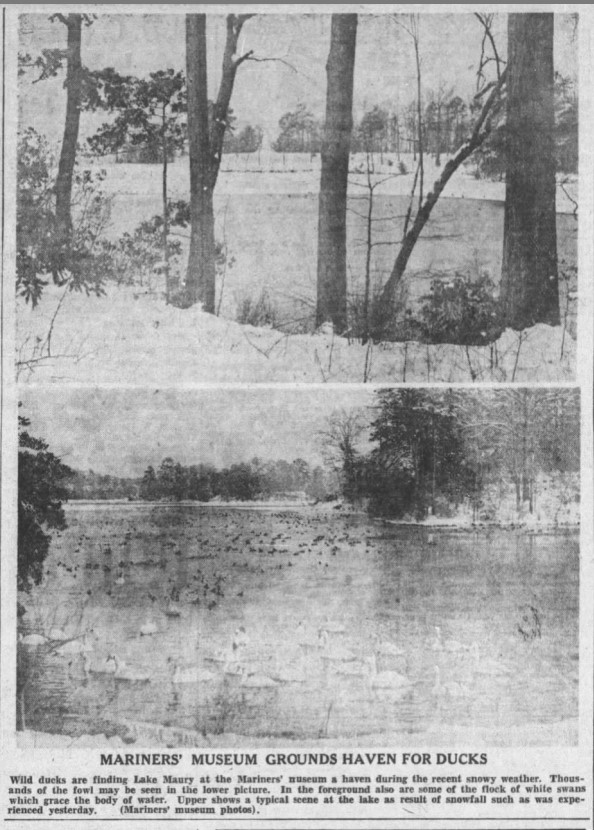

With the USDA permit for waterfowl, we had to submit a yearly report of the amount of each species present in the Park. The reports illustrate how immense our waterfowl populations became. Below are the largest numbers.

| Report Year | Number of Waterfowl Seen |

| 1933 | 600 Miscellaneous Ducks of Various Species |

| 1934 | 26 Canvasback and 24 Redhead Ducks |

| 1935 | 140 Quail and 24 Turkeys |

| 1936 | 1,300 Mallard Ducks |

| 1940 | 180 Canda Geese |

| 1943 | 31 Domestic Swans |

As funding shifted towards building the collection for the Museum, waterfowl numbers declined. In 1940, we gave up our wildlife sanctuary permit and stopped keeping wildlife by 1950. However, today we have attracted an array of different species to the Park with our natural resources.

To learn more about our species you can read this blog, here, or go to iNaturalist and eBird to look at citizen science data from the Park.