What’s your New Year’s resolution? I’m not great about setting personal resolutions, but we do have one for USS Monitor; 2021 is the year of rope! This year the archaeological conservators are working together, separately, to finish all of the rope fragments in our walk-in fridge.

Normally our yearly work plan focuses on the larger items which require multiple people. We then fill in our extra time with smaller artifacts. Because of social distancing and limiting people in the lab space, this project is a great alternative. The four of us will work together on our own time to treat the remaining 90 accessioned rope pieces. Not only will this free up space in our cold storage area, but it means that an entire material type will be treated and available for research.

This project is possible now partly because we’ve already tested the best methods for batch treating Monitor’s rope. Over the years the field has worked together, by sharing their experiment and treatment results to standardize methodologies. However, once you’ve narrowed down the options it’s wise to test them on samples of your material before starting new treatments. Archaeological sites have unique formations, mineralogical compositions, oxygen levels, etc. This means that a chemical or concentration that worked well for a particular site may not be suitable for a different site. Testing is an essential part of the process.

Last year I tested removing iron staining from ropes. During burial, organics absorb salts, minerals, and metallic ions from their surroundings. These contaminants must be washed out of the object before it is dried. If left, they will cause serious damage post-treatment. Iron corrosion is particularly difficult to remove.

I used 33 pieces of rope from Monitor and took them through the normal treatment process, testing 11 different solutions for removing the iron ions. Mymain goal was the removal of iron staining, but I was also interested in the physical characteristics of the dried rope. Is it flexible or stiff? Did it retain color or was it bleached? The goal of archaeological conservation is to stabilize an object while retaining its inherent characteristics.

The project took several months since iron staining removal requires soaking in solutions that sequester (or capture) metal ions and suspend them in solution. After this process, the rope needs to be rinsed in fresh water to ensure all of the sequestering agent and iron ions have been removed. The rope was then submerged in consolidant baths and finally freeze-dried. A consolidant replaces the water in a degraded organic and coats the cell walls. It prevents the cells from collapsing during drying, which happens when water is removed and the degraded cells cannot support their own weight. Consolidant testing occured the year before.

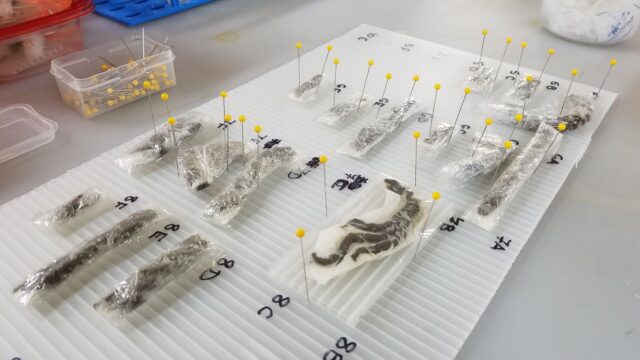

As you can see in the photo of the samples after freeze-drying, some solutions weren’t effective in removing iron staining. Others work really well. However, some of the ones that recorded high levels of iron removal also left the rope brittle. But in the end we found a few options that remove iron staining and retain the desired properties of the rope.

Now that the testing is over, we’re documenting the pieces before treatment. Photographs and written condition reports record the original condition, and can be compared with the after treatment condition. We’re also documenting features like size, type of twist, fiber identification, and any special features. This information provides insight into the types of cordage on board and their purposes. We can compare the data to historical records to add to the knowledge about life on board.